How visual storytelling can transform conservation communication.

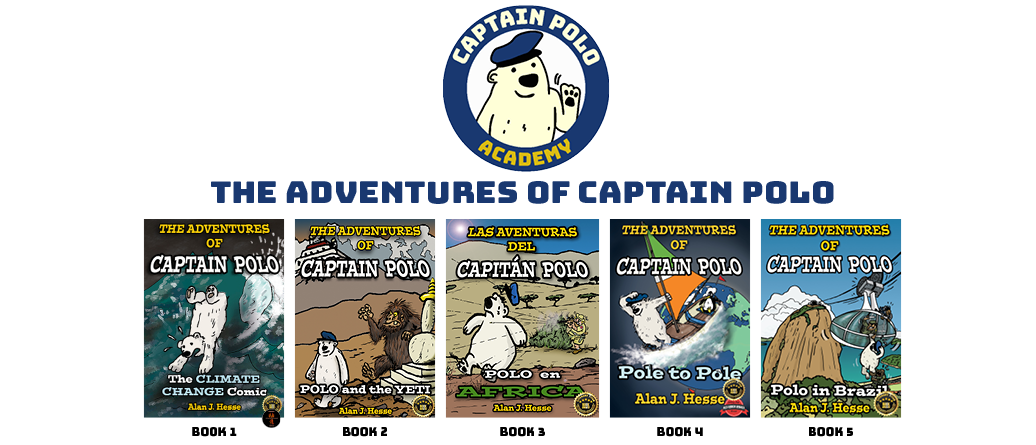

Meet Alan J. Hesse, a conservationist and storyteller who makes science fun. With over three decades of conservation work across Latin America, Alan has built a parallel career as an author-illustrator of environmentally themed graphic novels and children’s books. His Adventures of Captain Polo series blends humour, adventure, and solid climate science to engage readers of all ages. Based in Ecuador, Alan continues to expand the reach of conservation through his independent Captain Polo Academy and global partnerships.

Thejavitso: Can you briefly share about your journey from being a field biologist to becoming a conservation communicator?

Alan: My journey began with a Behavioural Science degree in 1992, followed by what was meant to be a three-month expedition to Bolivia. I stayed for 20 years, founding a conservation initiative for the critically endangered Blue-throated Macaw (Ara glaucogularis), then one of the world’s rarest birds. After a decade building the programme and learning on the job, I completed a Master’s in Conservation Biology, which opened new opportunities. Thanks to successive conservationists building on the foundations laid during those early years, the Blue-throated Macaw Program continues today, with the species slowly recovering. My shift toward conservation communication and education began in the early 2000s through a collaboration with Dr. Louise Emmons of the Smithsonian Institution. While supporting her research on Maned Wolves in northeast Bolivia, she encouraged me to turn her field findings into a comic for young readers. The result was ‘Fables of the Amazon: Fun Lessons in Ecology’', a unique blend of real field data, storytelling, and cartoons. Louise not only helped me begin this creative path—practically and personally—but also helped me believe in it. Things accelerated in 2009 when I co-created an environmental education consultancy with the Charles Darwin Foundation in the Galápagos. During four months on the islands, I produced a series of graphic novels that included the award-winning ‘Charles Darwin and the Theory of Natural Selection’. Peer-reviewed by evolutionary biologists at the Foundation and now published worldwide, the book remains one of my proudest works; a copy was even gifted to Sarah Darwin, Charles Darwin’s descendant. This period marked the true beginning of my graphic-novel career. After Galápagos, I returned to conservation practice, joining Rare to apply behaviour-change approaches across Latin America. Eight years later, I moved to TRAFFIC, where I now work globally as a Senior Behaviour Change Specialist.

Thejavitso: What inspired you to use illustrations/ graphic novels in communicating conservation?

Alan: Since childhood, I have developed a certain ability for drawing cartoons. Early in my career, while working in Bolivia on the Blue-throated macaws and other projects, I put some cartoons in some environmental education bulletins just to liven things up a bit and make the content less technical. It became clear to me that this was a unique and powerful way to communicate science that few were exploring.

Thejavitso: In your opinion, how does visual storytelling contribute uniquely to education compared to traditional scientific literature?

Alan: Scientific literature is made for scientists and at a stretch for policymakers. It doesn't reach people who are already invested in the subject. As any photographer knows, visual storytelling in contrast makes your work accessible to everyone. An image will cut through language and literacy barriers. Environmental stewardship is for everybody, not just professionals.

Thejavitso: Can you share from your experience on how you were able to help readers understand complex scientific information by using illustration?

Alan: Many adults who have read my Charles Darwin comic have told me that the format helped them for the first time understand Darwin’s legacy. To quote one reader from Amazon– “I thoroughly learned and enjoyed this graphic story of Charles Darwin by Alan J. Hesse. What fascinates me is how well the author tells the story graphically and compactly. Prior, I knew nothing much about Darwin, now I do.” I have got similar reactions concerning the Adventures of Captain Polo comics: A reader of the fourth Captain Polo book said, ”I highly recommend this graphic novel. I can’t emphasise enough how important reads like this can be in educating our children. I must confess, I also learned an awful lot when I read it too.”

Thejavitso: What kind of audience would you say you have engaged with the most (children, grad students, conservationists, policy makers, etc.,)? Which audience has your work resonated with the most?

Alan: My books target middle-grade children aged 9 to 12. Direct feedback from kids is limited due to restrictions on their contacting me, so most responses come from adults—parents and teachers who are ecologically aware and concerned. They provide the majority of my feedback. I know the books resonate with children because teachers have shared organised feedback indicating the kids enjoy the fun, humour, and adventure. I recently donated around 500 Captain Polo books to the Galápagos Infinito Project, which were donated to all the schools in the islands. However, the books haven’t yet connected much with policymakers. I wish they would. One adult reader even suggested these climate change books should be placed in front of politicians, and I agree with that sentiment. I must also mention a hand-written acknowledgement of the Captain Polo books received from Sir David Attenborough when he was gifted a copy; that’s a great honour!

Thejavitso: What are the most common mistakes people make when using visual media to communicate conservation messages?

Alan: A common mistake is leaving out essential storytelling elements. Many books include solid illustrations and science but still fall flat. Humour and adventure are crucial to keeping readers engaged. In The Adventures of Captain Polo: Pole to Pole, for instance, there’s a playful episode where Polo rescues the crew of a sinking Russian nuclear submarine—totally unrelated to climate change, but it adds energy and fun. Not everything needs to be technical. People often focus so much on the conservation message that they forget their audience, who may not be conservationists. The key is to make the message relevant by weaving it subtly into an entertaining story, so readers absorb it almost without noticing.

Thejavitso: Could you walk us through your creative process for one of your conservation stories?

I plan each book carefully, starting with the geography. I love maps and travel narratives, so the stories often span multiple countries. After mapping my character’s route, I research what’s happening along it—lately with a focus on climate change—and use this to shape the technical content. I then deepen the research and consult experts, especially from the Global South, including leading climate scientists such as Prof. Johan Rockström, the late Saleem Huq, and Clare Shakya. With the science in hand, I craft an accessible fictional narrative. I then map how text and images will fit together, sketch the storyboard, draw the artwork in Photoshop, and assemble the final book in Adobe InDesign.

Thejavitso: If you were to start your career with the knowledge and experience that you have now, what would you do differently?

I would have believed in myself more as a graphic novelist and not just a cartoonist. Cartoons are good but storytelling in graphic novels achieves far more. In conservation, I would say it’s a good

idea to consider studying for an MBA as well because an understanding of business is a tremendous asset in conservation.

Thejavitso: How do you see visual storytelling evolving as a tool for conservationists, educators, and scientists? Are there new platforms or mediums that excite you?

Animation has huge potential to turn books into engaging films, but it must avoid generic, overly AI-driven visuals. Originality—like hand-drawn or early Wallace and Gromit–style animation—still matters. Visual storytelling remains underused in conservation, even though films like Rio, The Lion King, and Finding Nemo show how environmental themes can be woven naturally into compelling stories. We need more of that.

Thejavitso: Are there any recent projects or collaborations you’re especially excited about that further your mission in conservation communication?

I recently completed a project with Biodiversity and the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture, supporting cacao farmers in Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador as climate change threatens this key chocolate-producing region. Through the Captain Polo Academy, I ran Train-the-Trainer workshops for community agroecology technicians and school teachers. We now hope to scale up the work, especially by involving women cacao producers interested in replicating the approach. I also launched my latest book, Captain Polo in Brazil, which also exists in Portuguese to reach a Brazilian readership.

Thejavitso: What is your ‘call to action’ you hope audiences will take away from your stories?

Firstly, the well-being of people and the planet is the responsibility of everyone, whatever your age, background, creed, or occupation. Secondly, if you discover you have a talent or a special skill or ability, use it for a higher purpose – whether that be to help people, to help wildlife, Nature, or whatever can make a difference to make the world a better place.

Thejavitso: Where can people learn more about your work and maybe connect with you?

The best place is www.captainpoloacademy.com. But you can also reach me on social media:

https://www.linkedin.com/in/alanjhesse1/

https://www.instagram.com/alanjameshesse/

https://www.facebook.com/alan.j.hesse/

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on WildHub, please sign in

Amazing interview, well done Thejavitso and thank you Alan for your time!

Thanks Liane, all congratulations to Thejavitso for his diligence on this!