Designing community programs for conservation

What are the key ingredients for sustainable change when engaging communities in ecosystem conservation?

I sought answers to this question through a series of interviews with field experts who work at the forefront of conservation with local communities across the Global South, often in challenging socio-cultural contexts. These best practices emerged from our conversations:

1. Engage local communities and understand their needs before starting the project

Before any conservation project takes off, it is essential to connect with local communities and truly understand their needs. When conservation interventions are designed without their input – even with the best intentions and community benefits in mind – they are more likely to fail. Responses to proposed changes can be quite unpredictable and good ideas fail in field implementation, if they do not involve communities in the planning phase. Imagine an NGO introducing coconut farming and not seeing much adoption, to later discover that the particular community is instead interested in developing a business around baked goods. Such examples are unfortunately quite common. Sharing initial ideas on interventions and opportunities with community leaders can uncover potential barriers before they obstruct progress.

A starting point for any intervention should be:

What is really important to this particular community?

Livelihood is a top priority. In cases of human-wildlife conflict people need to secure their means of living—imagine their farm having been trampled by elephants. Educational efforts are futile if basic needs are not met first. Alternative livelihood initiatives are sustainable only if the participating families are motivated and willing to invest significant time and effort. Various factors influence people’s decision-making when confronted with the choice of a different crop, adopting more environmentally-friendly farming techniques, or a completely new livelihood activity. One of the most influential factors is the perceived economic benefit. It is crucial to understand the community's perception of any planned intervention. During initial community engagement it is essential to identify members with the right attitude, skills and resources to undertake a new livelihood activity.

When aiming for behaviour change, for example to encourage farmers to adopt more sustainable agricultural practices, it is important to understand what drives current behaviours and what hinders change (e.g. loss aversion, lack of trust, perceived social norms etc). Knowing a particular community’s needs and behaviours lays the foundation for effective conservation activities.

2. Power-shifting and trust building are essential ingredients for change

Adopting a low profile when engaging with local communities is very important, though not always straightforward. Economic and educational gaps are prominent: locals often see conservationists as “the scientists who think they know it all and have come to educate us” or simply “the rich people from the city”, leading to initial mistrust. To bridge this gap, show respect, avoid speaking from an educator’s or scientist’s position of superiority. Refrain from trying to change any beliefs and practices. Instead, work collaboratively to incorporate their ways into the conservation project. Communities have co-existed with wildlife and share experiential knowledge of animals, their behaviour and daily routines. For example, they might know where elephants can be located at different times of the day and how they move through their land. Some communities have unique skills, like the indigenous Xikrin community in Brazil, who can navigate their dense forests like no one else. The Xikrin are able to detect human presence from campfire leftovers — even deep in the forest — so they can help with monitoring activities, to protect the forest from illegal logging and mining. When approaching communities for a conservation project, respecting and integrating their knowledge can make all the difference.

In one case, a conservation team faced initial scepticism when the locals thought they are only interested in their studies for their master’s thesis. To overcome this, finding a person who the community trusts to endorse the project was what made it happen. Depending on the context, the best people to approach might be the elders of the community, spiritual or religious leaders. This approach has also been described as “Conservation Evangelism”: engaging a religious authority that people will listen to and take as a source of truth.

Another notable example involves gaining the community’s attention through action: a conservation team from Sustainable Actions for Nature in Nigeria started by cleaning a beach. It was this action, rather than flyers or other environmental awareness materials that had impact:

Why are these people - who are not from here - cleaning the beach?

Curiosity led to trust as people saw the tangible benefits of a clean environment. Maintaining the power shift throughout the project is vital. For example, when delivering trainings, rather than a top-down approach, the workshop style should make people feel that:

We are sharing knowledge together.

When moments of friction arise, conservationists should present the issue to the community and enable them to solve it, without assigning blame or assuming a position of power.

3. Social inclusion and bringing information to life

Involving women and children in community meetings – especially when these usually only happen among a group of men or elders – increases inclusion and engagement with the project. The meeting then becomes “an event, where everyone is invited to attend”.

Children in particular are often curious and open to new learnings. By gaining knowledge, connecting with nature and wildlife, they can help activate much needed behavioural changes within their families: “My dad brought an impala and I told him that it was wrong!”

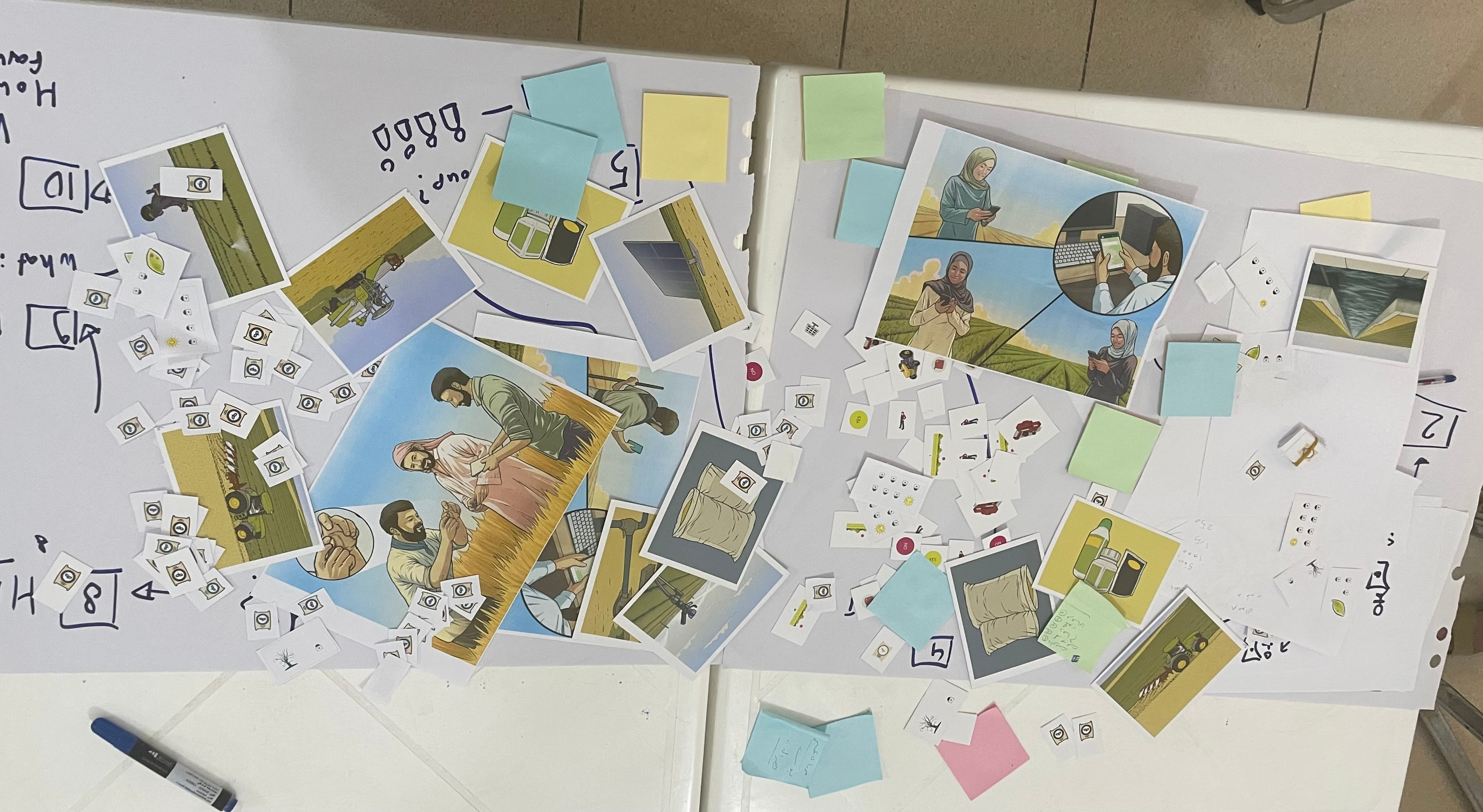

Overcoming linguistic, literacy, and other communication barriers is crucial when running activities in remote and culturally diverse communities. Visual materials, videos, and storytelling in the local language are powerful means to explain key concepts about wildlife behavior and ecosystem conservation. Role play can take this a step further. In Uganda, there are many venomous snakes and a common behavioural barrier is people’s tendency to throw stones and try to kill a snake at sight – resulting in numerous snake bites and deaths. To discourage this behaviour, the Herp Fauna Foundation runs demo sessions in communities, showing how to stay calm and move away from a snake to avoid getting bitten. Seeing how differently a snake behaves when it is not threatened, leaves a lasting impression in people’s minds. Being able to experience a non-venomous snake close-by, can bring empathy and regret: “This is so bad, we have been killing this poor snake all this time and it is not venomous!”

Poorly designed information materials can hinder behaviour change projects. In Nepal, Greenhood researchers found that rural communities struggled to understand new laws protecting medicinal plants. Some harvesters were unaware that the law applied to them, as they used a different name for a plant in their local language. Elderly harvesters (70-75 years old) found it hard to grasp how a practice that sustained them for most of their life could now be illegal. The team also discovered a monitoring gap: law enforcement officers had difficulties in identifying the plants during border inspections, because their manuals lacked sufficient photographs and practical information. It turned out that dried orchids in processed form looked very similar to potato plants! This case highlights the importance of community-specific awareness strategies and the need to test training materials with users to resolve ambiguities and improve comprehension through user feedback.

4. Consider the impact of local culture, customs and beliefs

Sometimes cultural beliefs and behaviours might hinder or delay the progress of a community program. Programs designed with a Western mindset often fail to anticipate potential socio-cultural barriers. Early cultural immersion, community engagement and participatory design can help mitigate such risks.

Cultural insights can guide better program design. In Africa, the long-held totem system has contributed to species and ecosystem diversity. Every person has a totem, represented by an animal which is considered sacred. One can never harm or eat their totem animal, which in the past ensured that some groups would not hunt particular animals – a kind of spiritual approach to conservation. Nowadays, conservationists can use totems creatively, for example by engaging leaders with specific endangered animals as totems to promote species protection. Cultural connections like this can boost environmental awareness, especially where communities are detached from nature and wildlife protection is limited.

Another example comes from a project aiming to provide a sustainable livelihood for the Xikrin, an indigenous community harvesting Brazil nuts. The community lives in an indigenous territory in the state of Pará in Brazil that has been the target of intense deforestation, and illegal mining. The Xikrin associate the concept of “ownership” with “nurturing something”. When harvested nuts had to be kept in a village storage facility (the ‘paiol’) prior to transportation, some community members would still take out nuts, despite the fact that the nuts had already been sold. This completely new model of storage and trade was hard to grasp and community meetings were necessary to address the confusion:

If these nuts are no longer ours, then why are we taking care of them?

Concepts that we take for granted can be interpreted in unexpected ways. Working with communities to figure out details can smooth such complex transitions.

5. Monitor progress & give feedback during and after the project

Conservation interventions require time to assess their impact, often spanning over years. This might not align with the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) metrics and timeframes required for reporting purposes. But to achieve real impact, it is essential to revisit the communities, assess progress and provide feedback – even after the end of a project:

People need to feel that you are interested in their progress. That you actually care about their well-being.

“Showing up again” makes a difference – especially for awareness programs that often run as one-off engagements due to limited funds.

Successful community conservation programs require sustained effort and long timeframes. A participatory design approach to conservation from the very beginning, co-creating programs to protect and restore ecosystems together with local communities, can help remove some of the barriers and hurdles that lie ahead.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the following experts who generously shared stories from the field and their valuable reflections:

Jucimara Cavalcante, Research, Anthropology, Environmental sustainability

Emmanuel Mukasa, CEO, Herp Fauna Foundation

Vimbainashe (Nicky) Chitauro, Conservationist, Founder & Exec. Director WildEd.Zim

Reshu Bashyal, Research Fellow, Greenhood Nepal

Grace Alawa, Founder Sustainable Actions for Nature

Kate Tointon, Communications Executive - Conservation Leadership Programme (CLP) at Fauna & Flora

Curious to learn how participatory design and co-creation techniques can be applied to community conservation?

Reach out to explore innovative approaches to community programming: yanna@designfollowsinsight.com

https://designfollowsinsight.com/

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on WildHub, please sign in

I liked practical part of the texts, that is very usefull. Great

Many thanks for sharing this very useful information and findings of your research, Yanna! Much appreciated. How have you experienced the process?

Hi Thirza,

My apologies for the delayed response, I just saw your question now, the notification email had somehow ended up in spam! Thank you so much for your positive feedback.

I really loved talking to the field experts, hearing their stories, their challenges and successes. I believe their amazing knowledge and expertise is reflected in these insights. I think this piece of research would benefit also from some conservation sponsor/leading organisation perspectives to help identify gaps between strategy & project design and field implementation, when it comes to community programs.

Hello - @Yanna Vogiazou. It's just so impactful up there. Please do you offer any courses on WildHub on this, or could you share any materials related to this or if you might be open to mentoring on similar initiatives???. Thanks

Hi @Wongibe Poupezo Dieudonne

I am afraid I do not offer any courses on WildHub, but I am currently looking for funding in order to build an online course specialising on designing community programs. In terms of resources, I recommend that you download the Stakeholder Engagement guidelines PDF from WildTeam as a starting point :-) Here is the link: https://www.wildteam.org.uk/conservation-best-practice-stakeholder-engagement

I hope this helps!

Thanks very much @Yanna Vogiazou. I will do so. Thanks for sharing